Virtual exhibition "Visual linguistic autobiographies of exiled students"

Curator of the virtual exhibition: Prof. Dr. Sílvia Melo-Pfeifer, Universität Hamburg

Contact: silvia.melo-pfeifer@uni-hamburg.de

1. Rationale of the exhibition

This virtual exhibition on visual linguistic autobiographies of exiled students, organized by the AGILE project, presents visual narratives created by students who have experienced exile, migration, or forced displacement, using their own drawings to tell the story of their linguistic journeys. Students’ contributions visually and emotionally capture their plurilingualism as lived, coupled with the contingencies of geographical and emotional displacements. In the AGILEproject, we see exile as a moment of transition in linguistic biography that has an impact on the formation and transformation of individuals, including at the linguistic level: “ecological transition”, as we see it, “occurs whenever a person’s position in the ecological environment is altered as a result of a change in role, setting, or both.” (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, p. 26).

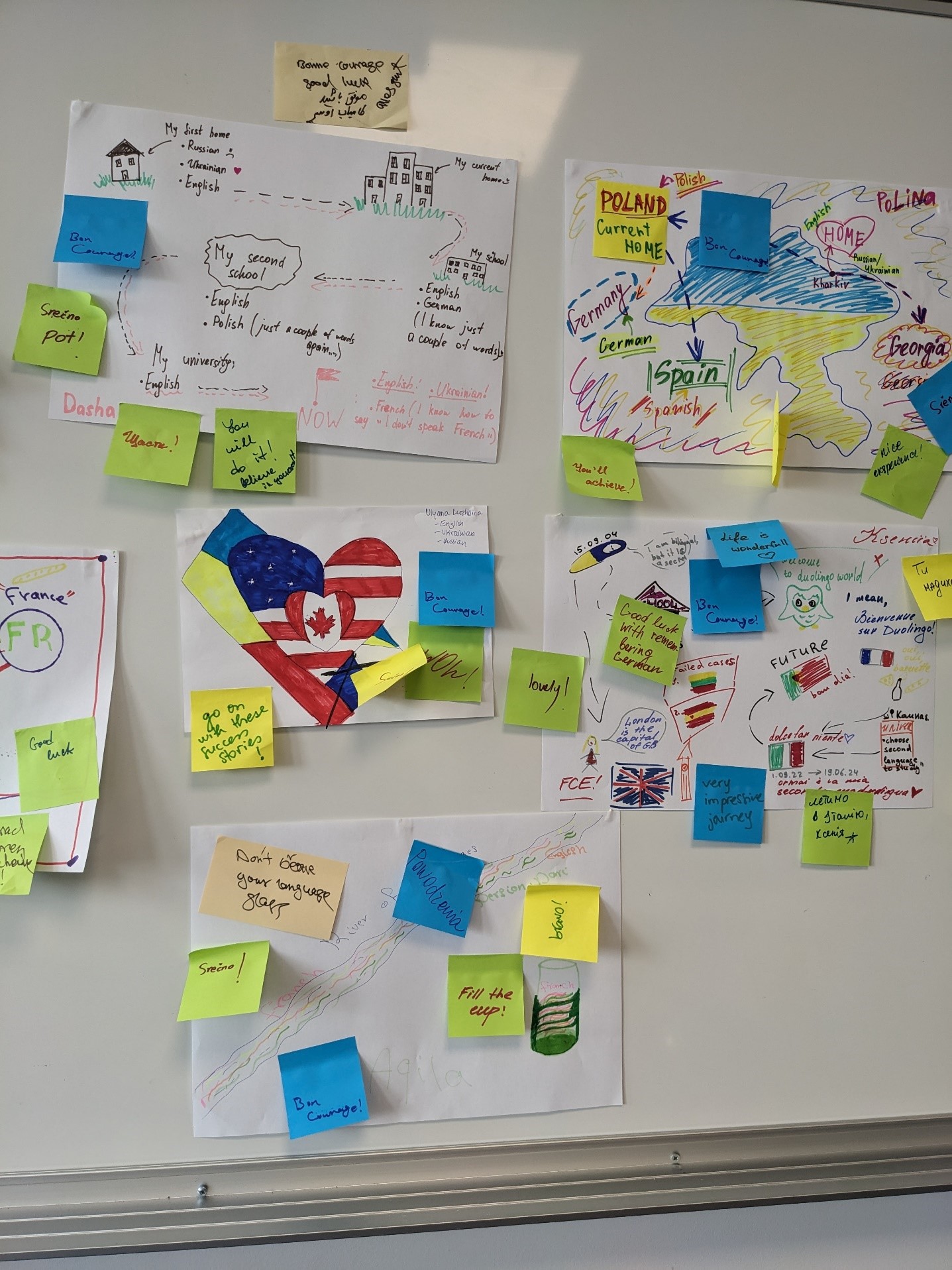

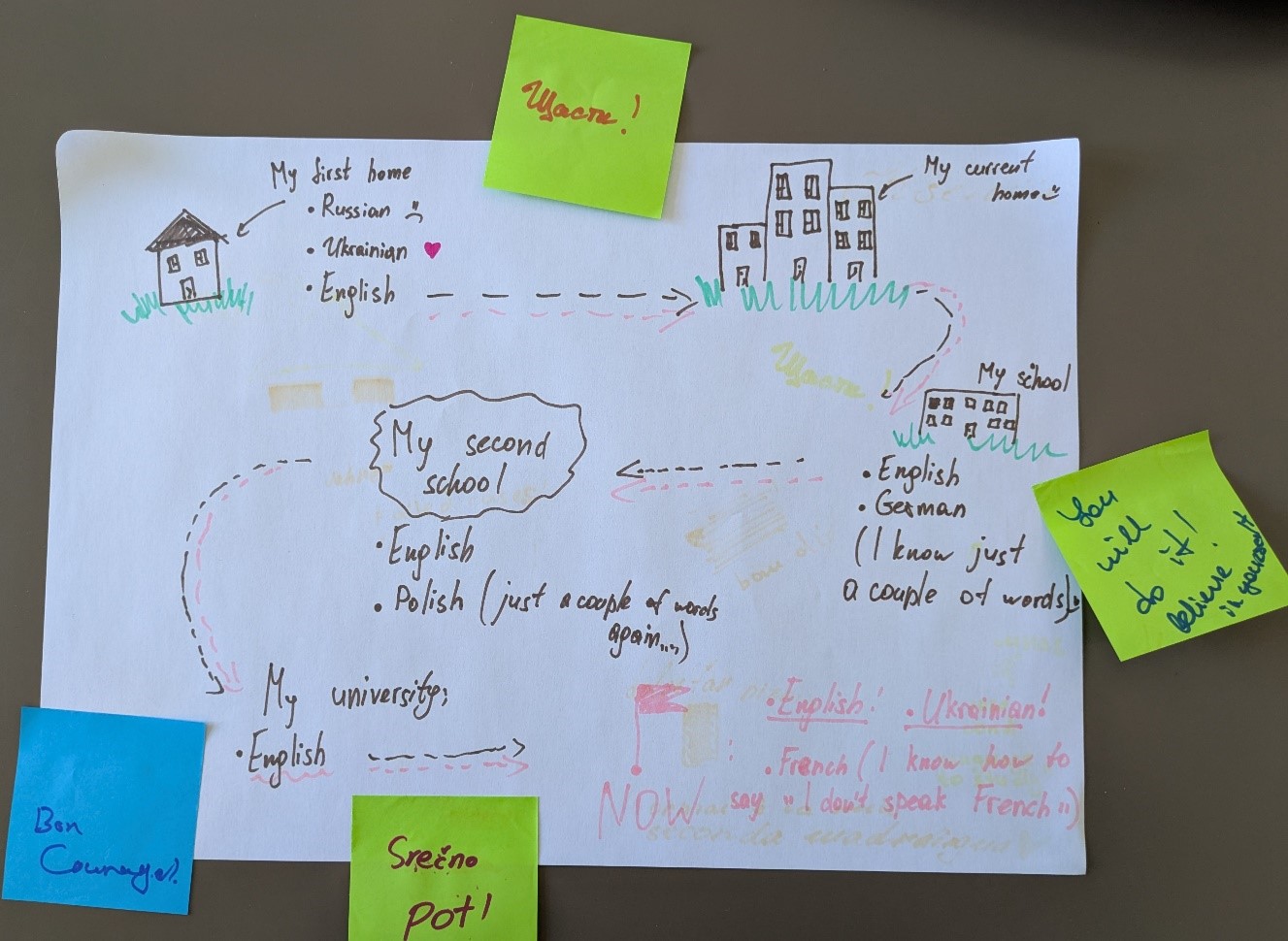

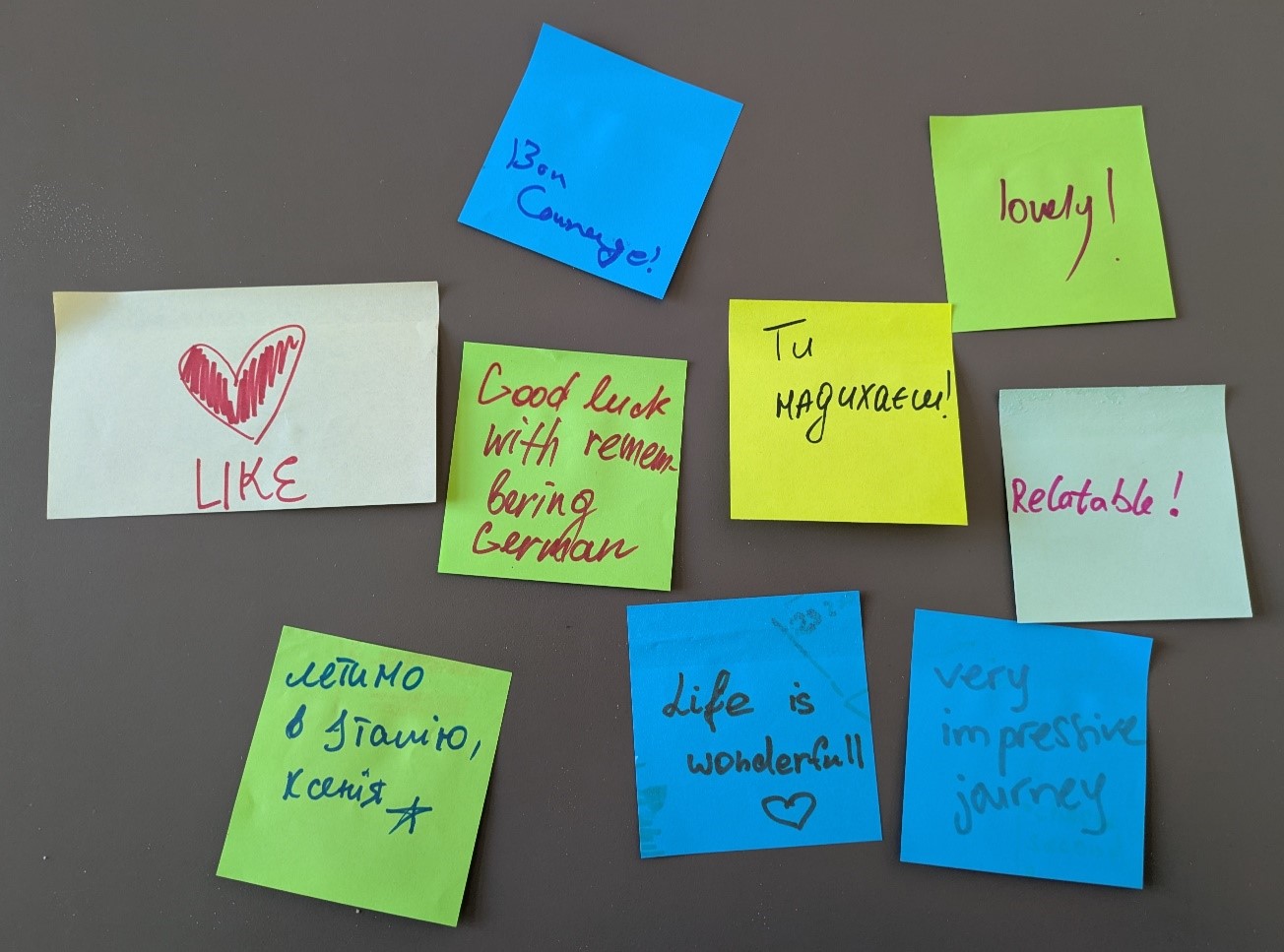

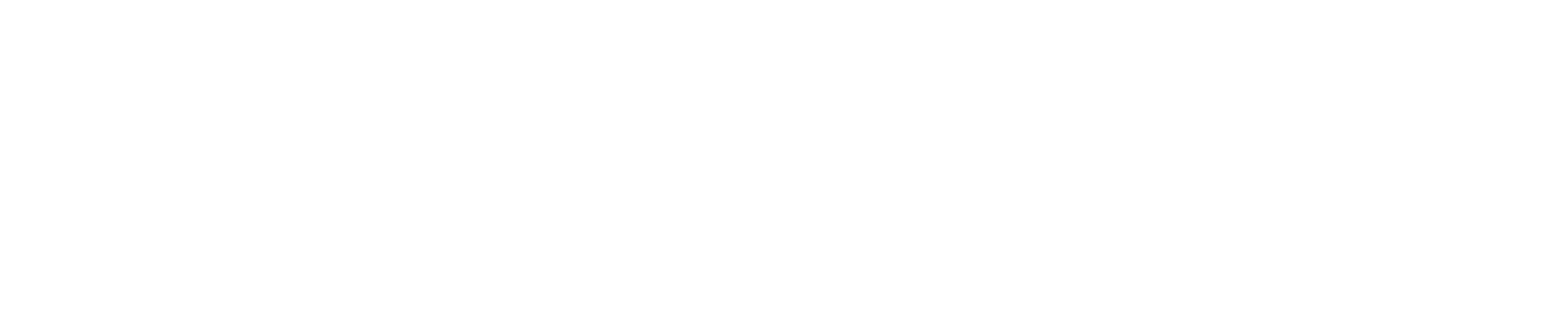

Data for this virtual exhibition was obtained during the AGILE summer school, in June 2024, and a total of 43 drawings were collected. The individual drawings were commented by the other participants in the summer school, through the writing or otherwise visually representation of feedback in colourful post-its (Figure 2). The workshop was carried out in English, but the students could leave the comments in any language. The traces of these feedbacks were left in this virtual exhibition. The organizers also collected photos of the exhibition, during and after the production, and videos of the presentations of each drawing by the students. The figures bellow provide two examples of the making-off of the drawings figure1) and how they were displayed at the end, in the room, as a collaborative tapestry of linguistic biographies (figure 2):

Figure 1. Making off.

Figure 2. The collaborative tapestry of linguistic biographies.

In this exhibition, students do not only document their linguistic repertoires but show how languages are entangled with exile, memory, power and empowerment, and identity, making visible what often remains invisible in typical educational settings. The aim of the organizers of this exhibition is to highlight exile not just as loss, but as transformation, showing how exiled students are not just surviving linguistic displacement but reshaping what language, belonging, and language education can mean for them.

This exhibition showcases exiled students’ productions around several thematic strands. First, the changing relationships with languages, ranging from losing to maintaining and resisting languages. The second strand is related to emotional landscapes tied to languages, encompassing representations and stereotypes attached to languages and cultures. A third strand relates to times, places and spaces where languages are learnt and used. A fourth a final section is related to developing strength and resilience through languages, referring to how exiled students use language(s) creatively to rebuild identity, belonging, and voice.

2. About the use of arts-based approaches with students in exile

The drawings that compose this virtual exhibition are part of a visual turn in education and embrace arts-based approaches to how we get to apprehend linguistic realities and changes in sociolinguistic identity. Drawings are non-logocentric expressions of the symbolic and the ineffable, an alternative/complementary means of expression when linguistic resources seem insufficient, what might be the case of exiled students still learning the language(s) used in the research.

Additionally, in cases of individuals experiencing sociolinguistic identity breakdown, drawings are a form of artistic expression that does not reinforce the feeling of having to produce in another language in order to talk about oneself. Visual language narratives thus have the power to illustrate how subjects initially perceive a kind of sociolinguistic disintegration, shaking their pre-exile certainties about language(s), imagined trajectories, and success, with a view to their academic, professional, and socio-affective integration in their host countries.

3. A guided tour through the visual exhibition

3.1. Thematic strand 1. The changing relationships with languages

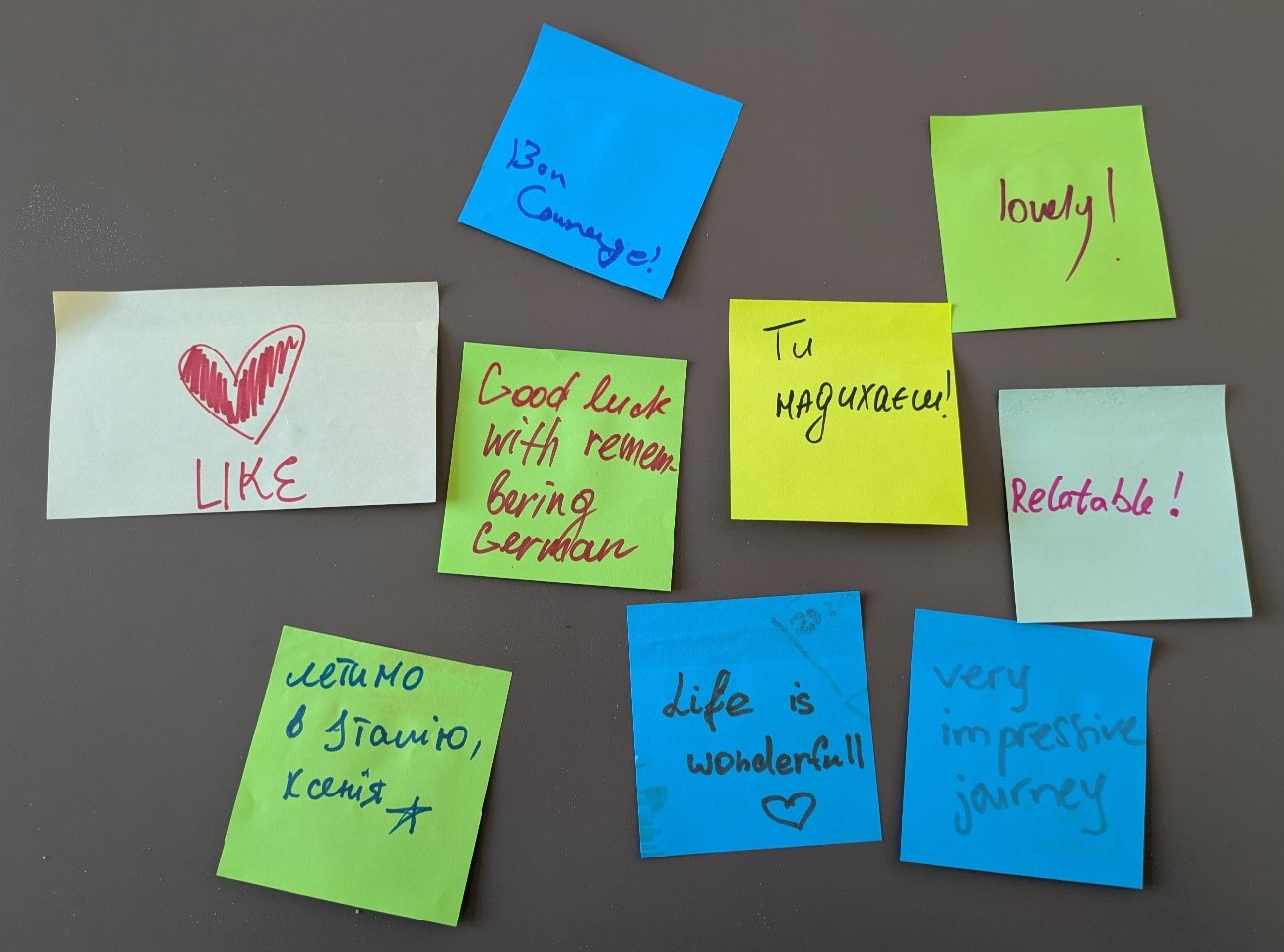

“The changing relationships with languages” refers to how individuals’ emotional, cognitive, and social connections to different languages evolve over time, particularly in response to life experiences like migration, education, exile, or shifts in identity. In Figure 3, the student represents a tree shedding its leaves as a metaphor for the loss of languages throughout her experiences of mobility. Each fallen leaf symbolizes a language or a linguistic connection that has faded or been weakened as a result of moving between different places, cultures, and linguistic environments. The tree, though still standing, is visibly affected by these transitions: its loss of foliage might reflect the emotional and cognitive impact of linguistic displacement.

Figure 3. The falling leaves.

This visual and organic metaphor conveys the idea that mobility, particularly when it is imposed or experienced under difficult conditions, can be associated to the erosion of previously rooted linguistic identities. The reference to this imagery in the feedback highlights the deep resonance of this representation with experiences of linguistic vulnerability and emotional dislocation of the other participants in the summer school.

Sometimes participants also draw their frustration at having certain languages included in their repertoire, as in Figures 4 and 5. In these two particular cases, participants express their rejection of the language they consider to be that of the invader (following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine), and therefore the source of their forced displacement. The detail of the visual biography in Figure 4 shows the Russian flag being erased, as a synecdoche for the erasure of the language itself from the repertoire, alongside the representation of destruction and the erasure of good things, such as the sun.

Figure 4. Destruction and linguistic denial.

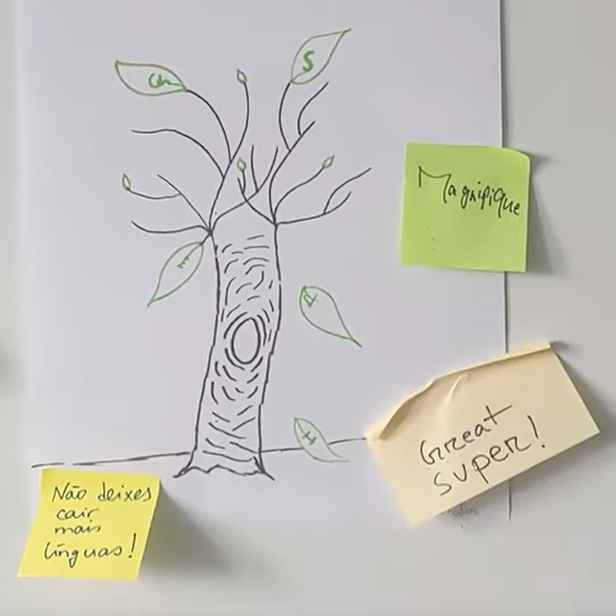

The same feeling of rejection of the Russian language is even more explicitly represented in Figure 5. Where the Russian language is depicted, the author writes “Russian: ‘I would rather forget’, ‘Russian should not be here’”. Contrary to the other languages, the Russian flag is not represented, an explicit erasure by the author.

Figure 5. Deleting languages of the plurilingual repertoire.

Unlike the other languages, which may be shown more neutrally or even positively, Russian is explicitly associated with negative emotions: the phrases “I would rather forget” and “Russian should not be here” show that the author feels a strong desire to distance themselves from the Russian language. Altogether, both the words and the visual choices (deleting and erasing) make the rejection of Russian very explicit, suggesting deep emotional, political, or identity-based tensions linked to the language.

While the author expresses rejection and symbolic erasure of the Russian language, a contrasting emotional relationship emerges with Polish. In presenting his drawing, after the production phase, he speaks of Polish with familiarity, pride, and a sense of belonging: “Of course I speak Polish (...) I am studying Polish for three years (...) It is very similar to Ukrainian. 60% of the language sounds the same (...) We just change a little the way we speak.” This commentary shows that Polish is not perceived as an imposed or foreign language, but rather as a bridge language, one that is close enough to Ukrainian to feel familiar, yet distinct enough to represent a new, affirming phase of his life. It signals a process of reterritorialization through language.

3.2. Thematic strand 2. Emotional landscapes

In the previous thematic strand, we could see how, in the same visual linguistic biography, two opposite emotional dynamics was made visible: the erasure of a language tied to trauma and oppression (Russian), and the embrace of a new language (Polish) that fosters continuity, belonging, and emotional reconstruction. This contrast highlights how language learning and language attitudes are deeply connected to migration experiences, identity negotiations, and emotional landscapes.

The same construction of emotional bonds to languages is represented in Figures 6 and 7, where new languages and linguistic experiences are attached to symbols and cultural representations of new lived contacts with languages.

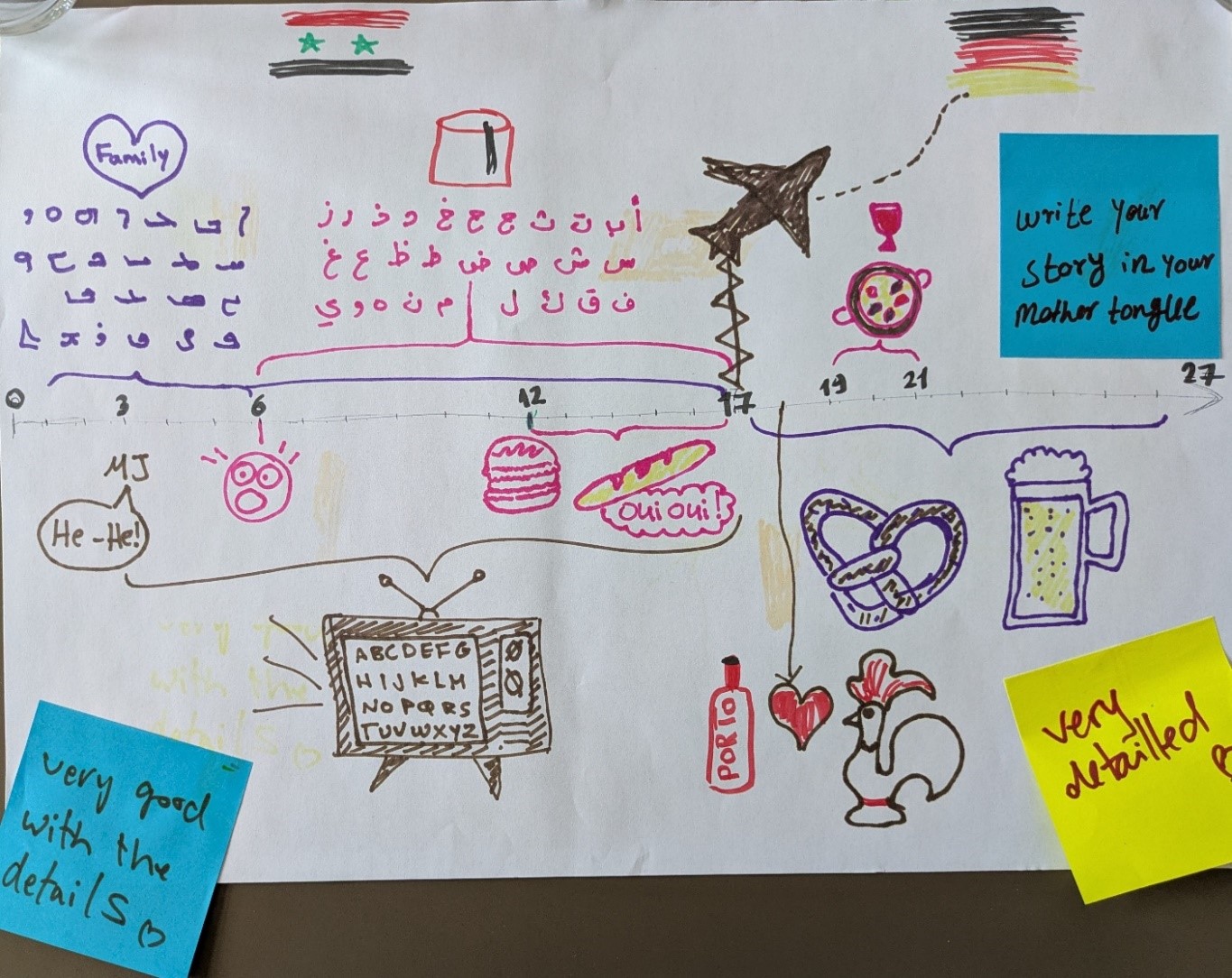

In Figure 6, the student visually represents the flags of their home country (Syria) and their host country (Germany), establishing an immediate connection between linguistic experience and national belonging. However, the linguistic biography portrayed transcends a simplistic or traditional association with the official languages of these two countries. Through a carefully constructed chronological line, the student maps out a much more complex linguistic life span, highlighting how languages are woven into personal, educational, and social trajectories. In addition to Arabic and German, the student depicts a minority language spoken in Syria, to which a strong emotional bond is attached—specifically linked to family heritage and intimate cultural identity.

Figure 6. Emotional landscapes across life.

In Figure 6, the trajectory additionally includes the learning of English and French within formal educational settings, indicating early contact with global languages through institutionalized schooling. The linguistic repertoire expands even further with the inclusion of Portuguese, acquired informally through personal relationships. This language is symbolized by vivid cultural icons, such as a heart (representing affection and emotional connection), a bottle of Port wine, and the “Galo de Barcelos”, a traditional Portuguese symbol. Together, these elements illustrate a multilingual and multicultural life path that resists national borders, emphasizing how personal relationships, emotional attachments, and cultural exchanges dynamically shape linguistic repertoires of exiled students, beyond formal and expected channels.

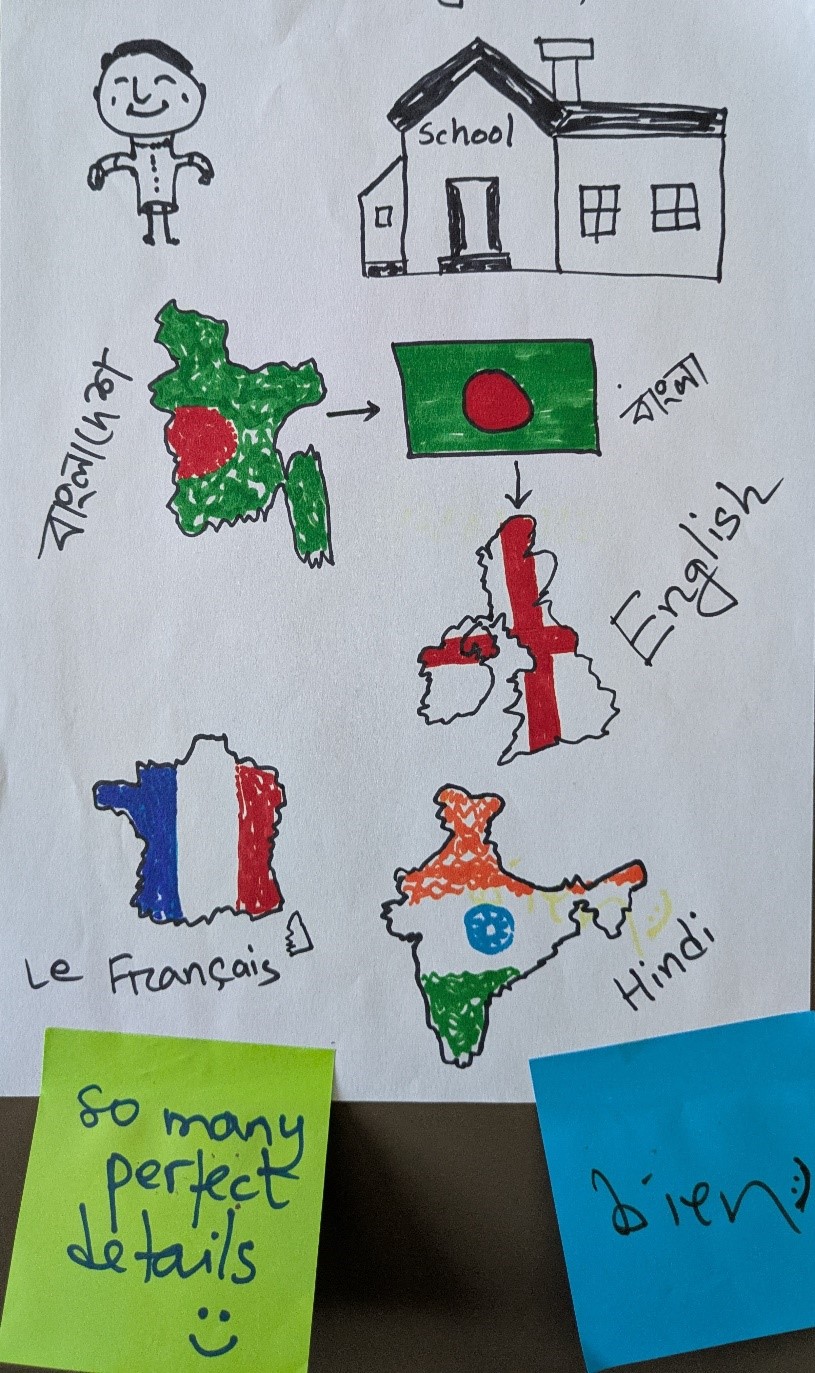

Figure 7 visually represents the student’s contact with at least four distinct linguistic geographies, narrating a story of multilingual and multicultural experience. The drawing begins with a happy face connected to the concept of school, indicating that the student’s early linguistic experiences were associated with positive emotions and structured learning environments. From this starting point, the visual narrative is organized using arrows that trace the student’s journey: first highlighting an initial connection to Bangladesh, likely reflecting the student’s heritage or early family language experiences.

Figure 7. Emotional landscapes across borders.

Following this, the arrows lead to England, suggesting either migration, a period of residence, or a significant educational and linguistic immersion in an English-speaking environment. Interestingly, the French and Indian flags are placed within the same horizontal frame of the drawing, indicating that the student’s contact with these two languages or cultures occurred simultaneously or during overlapping periods. This spatial arrangement on the page suggests a period of linguistic and cultural plurality, where multiple identities and language experiences coexist rather than succeeding one another chronologically.

3.3. Thematic strand 3. Times, places and spaces

The images reproduced here, although they allude, as in the case of Figures 4 and 5, to situations of violence and war, do not portray the exiled students as witnesses or direct victims of war. However, war is the most commonly represented trigger to explain the reason for displacement. This section provides an analytical framework for examining how flight, as a moment of transition, impacts linguistic biographies. The images and transitional spaces reflect the intricate relationship between geography, language, and identity during moments of forced mobility, highlighting both the challenges and resilience involved in navigating these shifts.

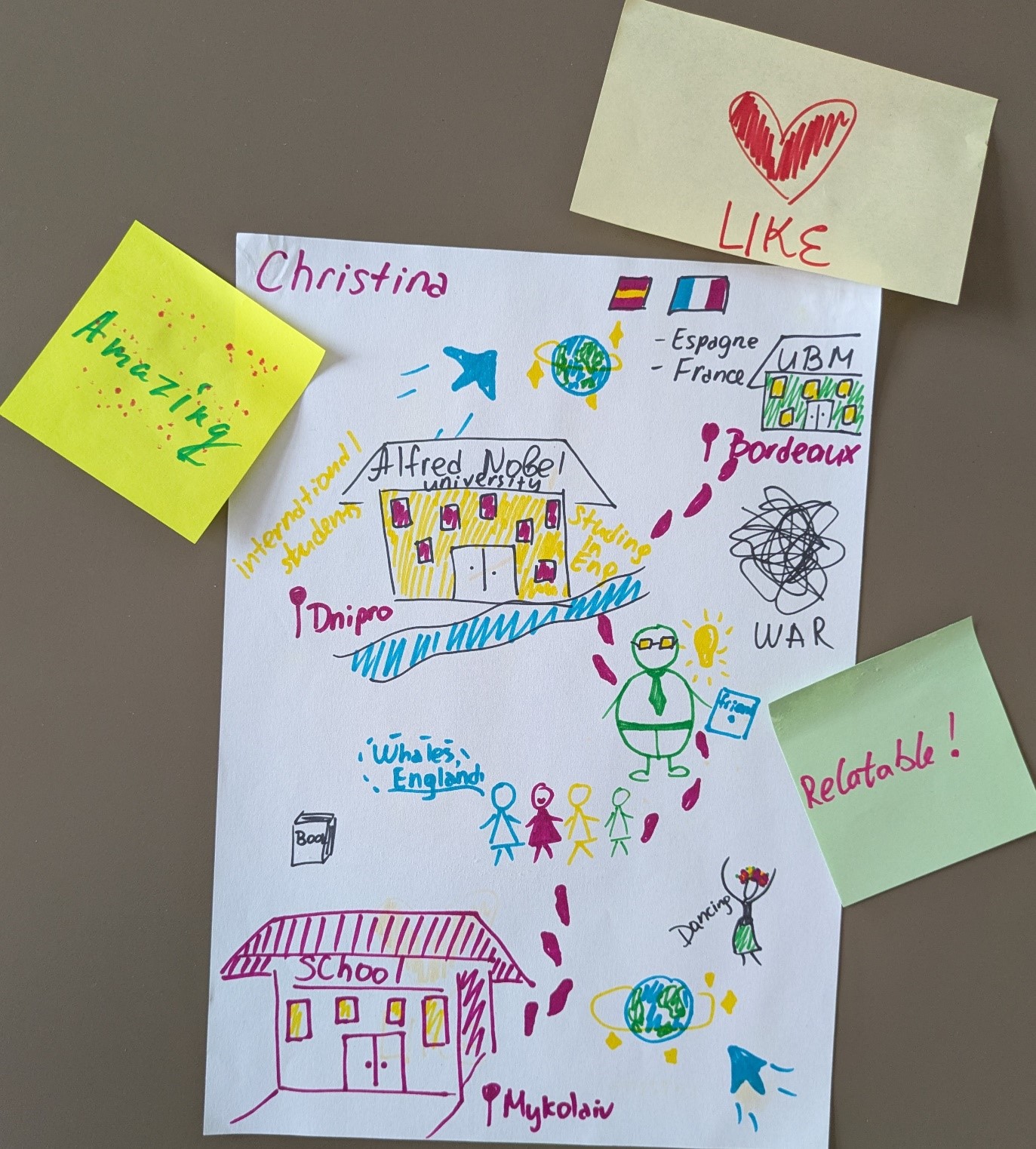

Figure 8 reads bottom up, and starts with the representation of school and extracurricular dancing activities. The path of the student is represented through footsteps, which cross the river to study in Dnipro, at the Alfred Nobel University. The war is then represented as the turning point in the academic path, leading the student to a French University, where the student also come into contact with Spanish and French.

Figure 8. Disruption caused by war.

The image’s bottom-up reading suggests that the student’s life begins with the foundational experiences of schooling and extracurricular activities, grounding the narrative in their early education and sense of belonging. The visual biography tells a story of forced migration, where the war disrupts the student’s original academic trajectory, leading them to a new educational environment and new languages. The image of crossing the river, encountering war, and ultimately finding new paths in education and language evokes the theme of displacement and the resilience required to build new (linguistic) identities in the face of forced mobility.

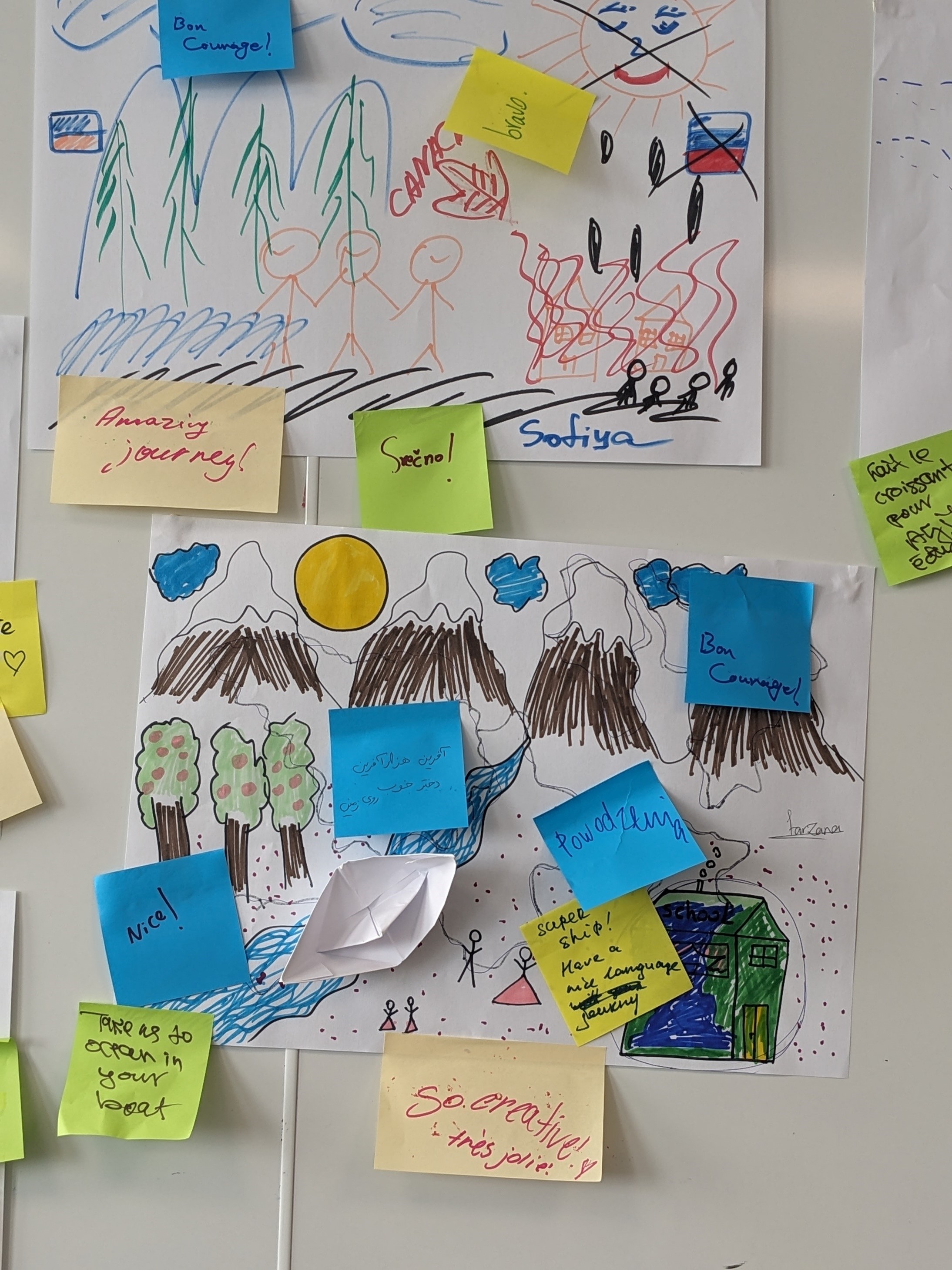

Some exiled students vividly capture the complexity of their journeys through multiple geographical and linguistic transitions in their biographies. Figure 9 exemplifies this layered experience, illustrating a series of displacements from Afghanistan to Austria and then to France.

Figure 9. Multiple transitions: from Afghanistan to Austria and France.

This linguistic biography portrays not only the physical movement across borders but also the accompanying linguistic and cultural shifts each relocation entails. The representation of these successive displacements highlights the resilience of the exiled student as he navigates the intersection of different cultures and languages, showing willingness to embrace new opportunities for the growing of the plurilingual repertoire.

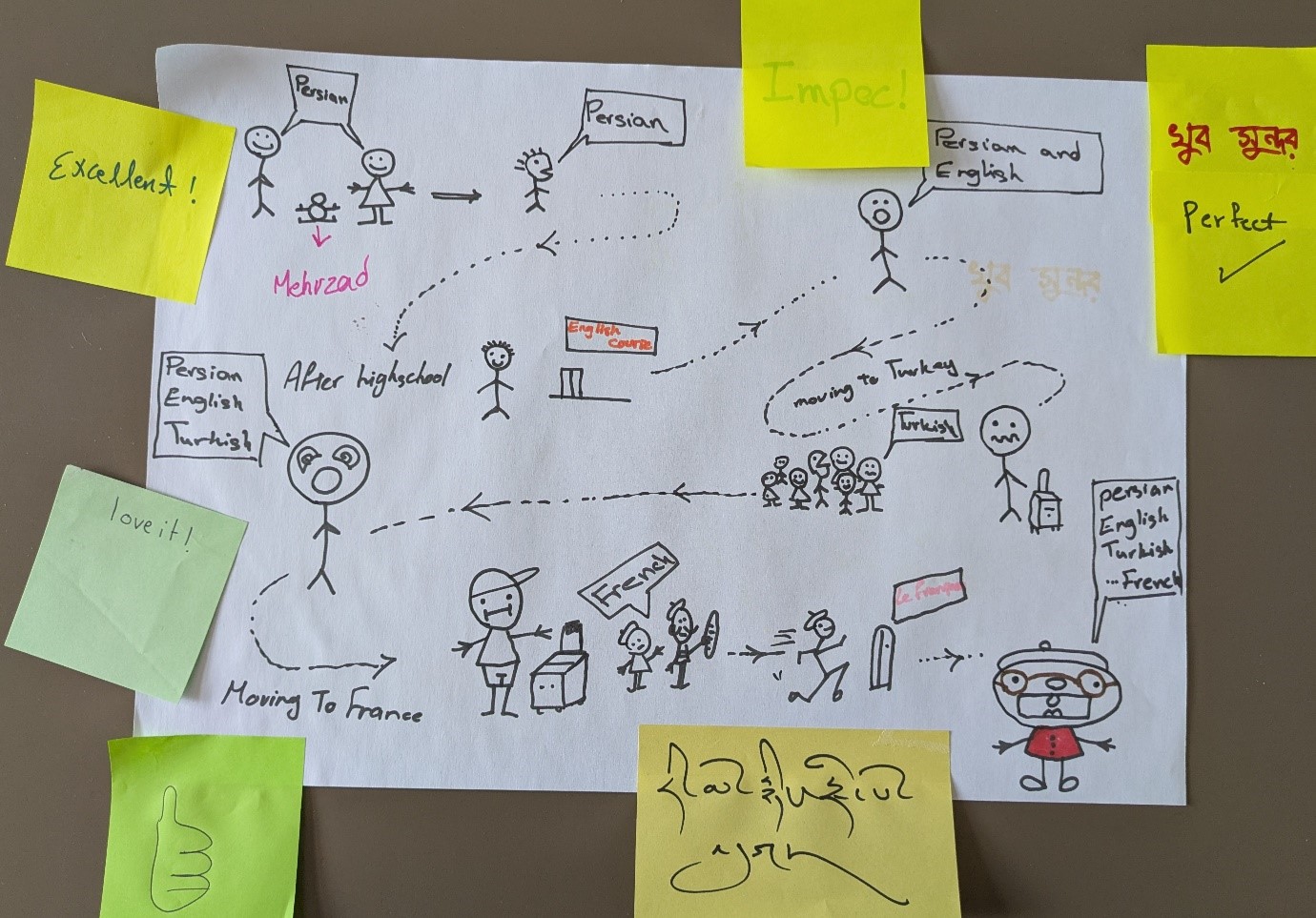

Figure 10 offers a powerful visual narrative of multiple displacements, reflecting both the emotional and linguistic transitions of the student’s journey from Iran to Turkey, and finally to France. Initially, the student illustrates a strong and positive connection to Persian, their mother tongue, in their home country, symbolizing a sense of familiarity and comfort. As the student faces the need to relocate to Turkey, the drawing shifts to a distressed expression, with luggage symbolizing the upheaval and the emotional turmoil of displacement. This moment marks the introduction of Turkish into the student’s linguistic repertoire, a language associated with the challenges of adjusting to a new country.

As the student continues their journey, the drawing moves to the final relocation to France, marking the next phase in their linguistic evolution. The student’s language profile evolves from monolingual (Persian) to bilingual (Persian and English), to trilingual (Persian, English, and Turkish), and eventually to a quadrilingual identity (Persian, English, Turkish, and French).

Figure 10. Multiple transitions: from Iran to Turkey and France.

This linguistic biography represents not only a linguistic transformation but also the adaptation and resilience of the student in navigating multiple linguistic landscapes. The drawing illustrates the student’s increasing ability to communicate in diverse cultural and social contexts, showcasing the complexity and fluidity of their linguistic identity as shaped by migration and displacement.

3.4. Thematic strand 4. Developing strength and resilience through languages

In this section, we comment on two drawings where exiled students show that learning and using multiple languages can help them build emotional, mental, and social resilience in the face of challenges. The comments and drawings presented so far have already addressed the theme of resilience and adaptation, showing that exiled students are not (only) victims of circumstances, but find opportunities for agency and investment in their new linguistic contexts.

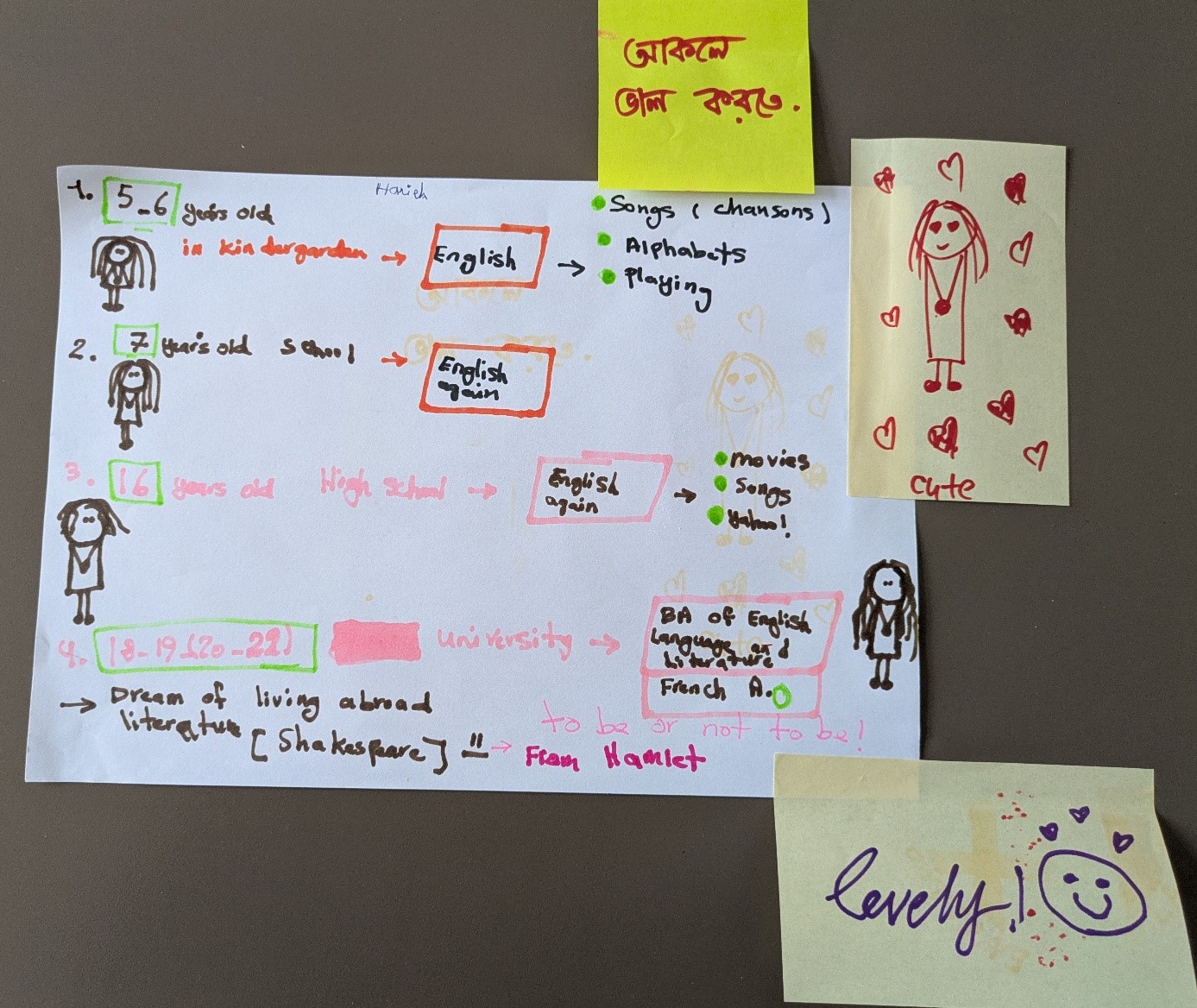

The student represents, in Figure 11, four phases in her life, where English is highly predominant. The student always represents new situations and opportunities for contact with this language and does not label herself as a refugee student, instead referring to the last phase of her life as “study abroad”.

Figure 11. Pursuing the dream of living abroad.

What is most striking about this drawing is not so much the accumulation of geographical movements and linguistic transitions (as we saw in some of the previous linguistic biographies), but rather the fact that, although she is collaborating with a project aimed at exiled students (the AGILE project), she seems to reject this designation for herself, positioning herself as an international student, “living abroad”. This shows that identities, even when imposed or assigned to participants, can be contested by them, subverted, and readapted to better fit the representations that students have of themselves. In this sense, this rejection of some labels and adoption of others shows how much agency students have and how they take ownership of their own paths and identities.

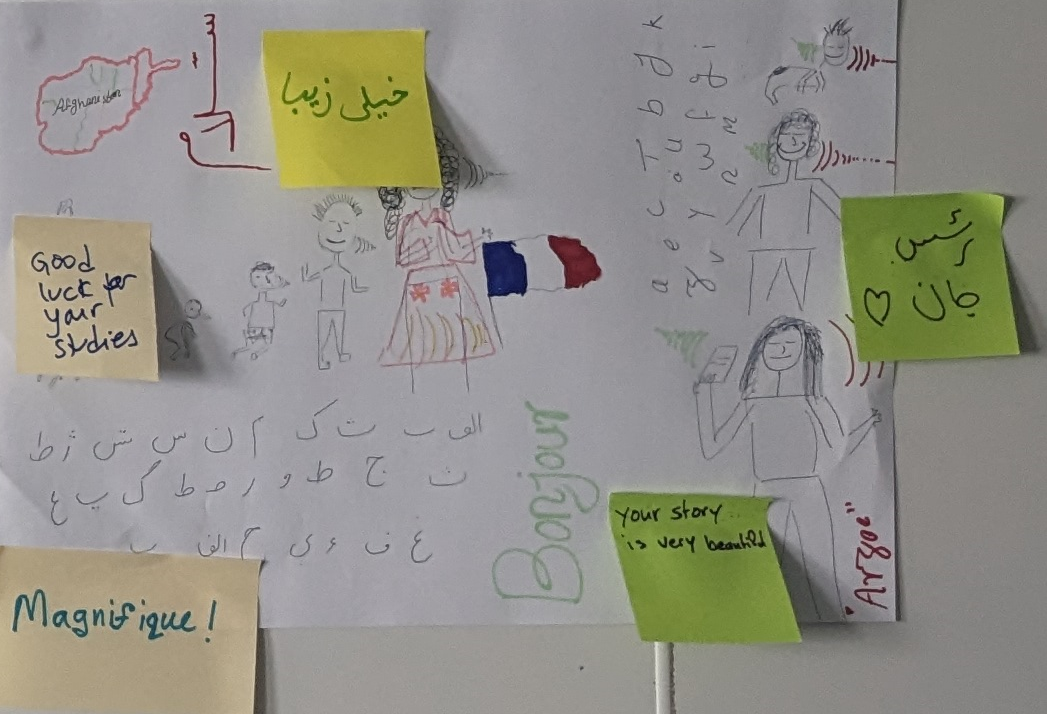

The next linguistic biography showcased in this virtual exhibition illustrates a pathway from Afghanistan to France (Figure 12). The student represents the growing from toddler to an adult woman, and having contact with the new language (also) through new technologies. These contacts with the new language (French, represented through the flag and the word “bonjour”) indicates the agency in learning and using the language.

Figure 12. Learning French.

Figure 13 offers a representation of a Ukrainian student’s linguistic biography, highlighting the emotional and geographical journey that shapes her identity. The student distinguishes between “my first home” and “my current home”, using visual symbols –a house for the first and an apartment for the current one –indicating a shift in both physical and emotional space. This distinction suggests that the student’s sense of home and belonging has evolved as she navigates their displacement.

Figure 13. Inter and intra border transitions.

The emotional weight assigned to languages is visually represented as well: Russian is depicted with an unhappy smile, signifying negative associations or feelings, likely related to the historical and ongoing conflict, while Ukrainian is represented with a red heart, symbolizing pride, attachment, and positive emotional connections to the native language. This emotional contrast reflects the complex relationship with language, particularly in a context of conflict and cultural identity.

Furthermore, the student’s transition from school to university in Poland underscores that these transitions are not solely about crossing national borders but also about moving between different stages and social contexts within a country. This emphasizes the concept of “inter-borders” and “intra-borders” transitions, where the shifts involve both geographical and social movements - transitions that occur not just from one country to another, but also between different levels of education and new phases in the exiled student’s life.

4. Before clicking on the logout button…

This exhibition highlights the added value of visualizing linguistic biographies by exiled students, where transitions offer powerful visions of deterritorialization and reterritorialization. Through the visual narratives, we witness the complex processes of moving from one territory to another, losing a familiar ground, and gradually finding one’s footing in new (linguistic) spaces. These individual and shared visualizations of life trajectories reveal not only the uniqueness of each student’s mobility experience but also the intersubjective ties –the “you in me” –that bind diverse experiences together.

The image emerges as a potent vector of movement, flow, trajectory, and interruptions in mobility (Borgé, 2020). The final mural (see Image 2), co-constructed by participants, stands as a vibrant “ethnoscape” (Appadurai, 1996 and, in our own words (Potolia, Melo-Pfeifer & Lawrence, 2024), an “ethnoEscape”: a space reflecting not only the diversity of identities but also the multiplicity of exile trajectories.

Throughout the exhibition, we encounter visualizations of forced hypermobility and traces of linguistic and geographical transitions, where drawings make visible the “identity breaches” (Baroni & Jeanneret, 2011) and the fragile, transitional spaces inhabited by exiled students. This virtual exhibition echoes the “mobility turn” (Molinié & Moore, 2020) in language and teacher education, drawing attention to the realities of forced, imposed, and involuntary movements, and calling for a more critical and empathetic understanding of mobility in language education.

As viewers also had the opportunity to see, the other participants in the drawing activity had the opportunity to comment on the drawings of the other exiled students. Go back and scroll down and think: think of Figure 14 and what comments would you leave to the authors of the drawings selected for this exhibition?

Figure 14. Leave a message.

References

- Allouache, F., Blondeau, N., Potolia, A., & Taourit, R. (2022). Autobiographies langagières : arrimages existentiels, transmissions, élaborations identitaires. Agencements, 7(1), 146-181. 10.3917/agen.007.0146

- Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at large. Cultural dimensions of globalization. University of Minnesota Press.

- Baroni, R., Jeanneret, T. (2011). Différences et pouvoirs du français. Biographie langagière et construction de genre. Dans Huver, E., Molinié, M. (dir.), Praticiens-chercheurs à l’écoute du sujet plurilingue. Réflexivité et interaction biographique en sociolinguistique et didactique (p. 101-115). Carnets d’Atelier de Sociolinguistique 4. https://univ-sorbonne-nouvelle.hal.science/hal-01873622/document

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

- Fillol, V. (2016). Les (auto)biographies langagières comme outil de lecture de la situation postcoloniale en Nouvelle-Calédonie et comme outil d’empowerment dans une démarche sociodidactique. Contextes et didactiques, 8.https://doi.org/10.4000/ced.615

- Molinié, M., & Moore, D. (2020). Mobilités, médiations, transformations en didactique des langues. Recherches et Applications, 11-20.

- Potolia, A., Melo-Pfeifer, S., & Lawrence, L. (2024). Autobiographies langagières d’étudiants exilés en Europe : récits de dés-/réagrégation des identités sociolinguistiques. Oral presentationat La Relation en Didactique des Langues, Paris/DILEC, 28 novembre 2024.

Related projects

- BOLD (“Building on Linguistic and Cultural Diversity for social action within and beyond European universities”), an Erasmus Plus project (2022-1-DE01-KA220-HED-000086001) related to social action and service learning in pre-service teacher education. URL: https://boldproject.eu/

- IDéAl (“Immersion - Défi - Alterité”), is a binational project (French and German), dealing with the building of the relationship with French and German by newly arrived children and adolescents. URL: https://www.ofaj.org/recherche-et-evaluation/projets-de-recherche/ideal-immersion-defi-alterite